Concurrency is often touted as a cure-all for improving the performance of software applications. On paper, it does sound perfect - you break down a problem into smaller bits and execute them at the same time, and boom - your program runs faster than a speeding bullet! However, it turns out things are not that simple. While concurrency can bring huge performance improvements if implemented correctly, like everything else, it brings its own set of problems.

One of the biggest limitations of concurrency is defined theoretically by Amdahl’s law. Before we dive into what this law has to say about concurrency, we need to understand that in most systems, we don’t have truly parallel requests, i.e., we often have some requests that run parallel while others are processed serially. This is relevant because Amdahl’s law states that the maximum speedup that can be achieved by adding more processors to a problem is limited by the amount of code that cannot be parallelized. In other words, the amount of code you can’t parallelize (i.e., the code that runs serially) limits how much faster your program can go. Even a small increase in the code that runs serially can have a disproportionate effect on the maximum speedup that can be achieved.

Maximum speedup refers to the maximum improvement in the performance of a system that can be achieved by parallelizing a portion of it.

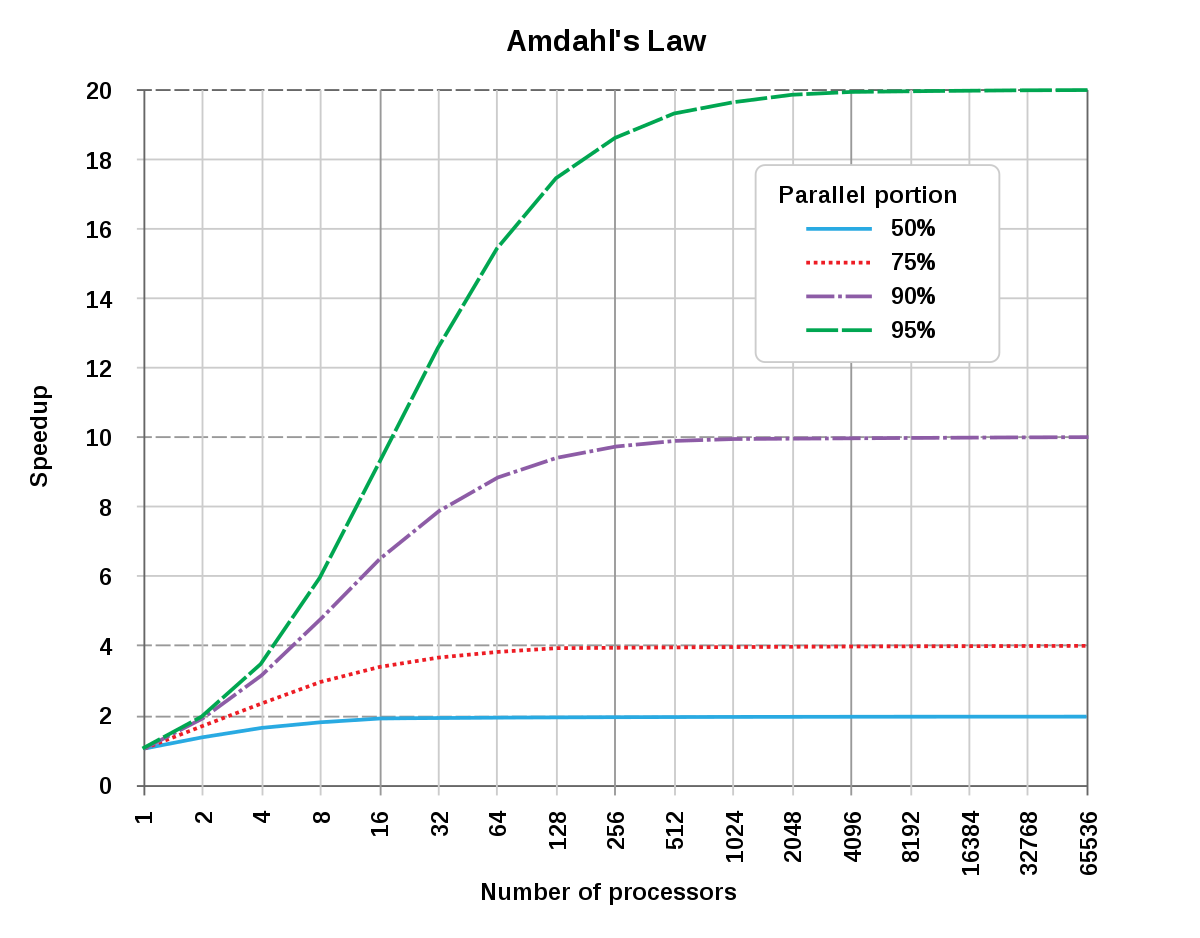

If my argument above is confusing or doesn’t sound too convincing, let’s look at the following graph

The y-axis represents the speedup, and the x-axis represents the number of processors. In this system, we assume that we have some percent of serial processes while the rest of the processes are parallel (the percent of the parallel portion is shown in the legend). When the percent of parallel processes is 95%, we observe that the speedup increases with the increase in the number of processors until a certain point, after which it flattens (We can calculate this point using Amdahl’s law). With 90% of parallel processes, the graph flattens much sooner. In other words, with only a 5% increase in the serial processes, the maximum speedup is reduced by 50%, and with 75% of parallel processes, the maximum speedup is almost as good as running all processes serially. This goes to show that while concurrency sounds attractive, the speedup you gain from it is, in most cases, only slightly better than true serial processes, and even a small amount of additional serial code can make the gains from concurrency minimal. Thus, even if you can parallelize the majority of your code, you may not see significant performance gains if there are small portions of the code that must be executed serially.

Another flaw with concurrency is that it can actually slow things down. This is because parallel execution comes with a bunch of overhead, like synchronization and communication between threads, which can consume your time and resources. Furthermore, concurrency can introduce subtle bugs and race conditions that can make your code more confusing to read, write and debug. When multiple threads are accessing shared resources, it can be difficult to ensure that they don’t interfere with each other in unexpected ways. You never know what order your threads will execute in, and this can lead to hard-to-diagnose bugs that only show up in certain conditions, or worse, data corruption that can cause serious problems.

But wait, there’s more! Not all problems are suited to parallel execution. Some just can’t be broken down into smaller pieces that can be executed at the same time. In these cases, using concurrency can make your problem more of a mess to the extent that the effort might not be worth it.

So, before you go all-in on concurrency, consider the complexity that concurrency brings and decide if this added complexity is really worth it.

Despite these challenges, however, there are still many cases where concurrency can be extremely useful. For example, tasks that involve a lot of I/O, such as reading from a file or making network requests, can often be parallelized effectively. This is because these tasks often involve a lot of waiting for external resources, which means that there is plenty of idle time that can be used to run other tasks in parallel. Concurrency can also be very useful for tasks that involve heavy computation, such as rendering complex graphics or simulating physical systems. In these cases, breaking the problem down into smaller pieces and executing them in parallel can allow you to take advantage of multiple CPU cores, which can significantly speed up the computation.